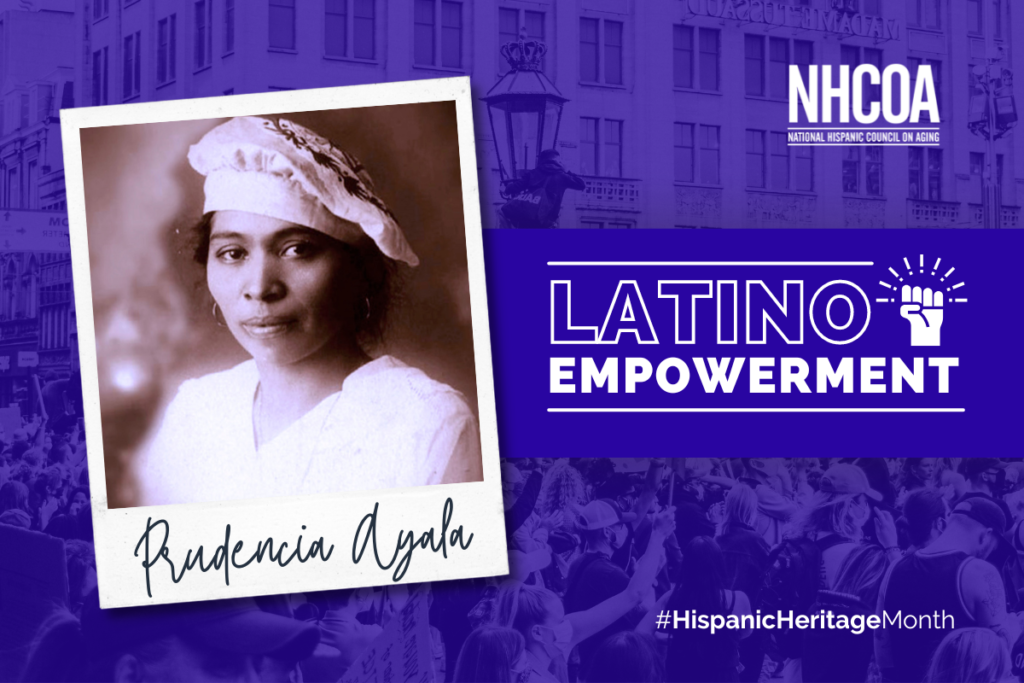

Prudencia Ayala was the first woman to seek the presidency of a Latin American country. She was born on April 28, 1885 in Sonzacate, El Salvador. She came from an indigenous family. When she was 10 years old, she moved with her mother to Santa Ana, a coffee town where she became acquainted with the trade union movement. Unable to finish the second grade due to the poverty of her family, her education was self-taught and she began to earn her living as a seamstress.

In 1898, at the age of 12, she began to have premonitions which began to be published in the Diario de Occidente of Santa Ana. Her prophecies were accurate with some events such as the fall of the Kaiser of Germany in 1914, which earned her the nickname Sibila Santaneca (Sibyl of Santa Ana).

Due to the success of her publications, the director of the Santa Ana newspaper, Rosendo Díaz, gave her a space in the editorials of the newspaper. He allowed her to publish, in different newspapers in Guatemala and El Salvador, her feminist ideas and her Central American unionist thoughts, as well as her ideas about equality between men and women, in addition to her poetry.

Ayala later became a single mother of two children and was a supporter of anti-imperialism, feminism, and Central American unionism. She also expressed her rejection of dictatorships and spoke out against the U.S. invasion of Nicaragua.

In 1919 she was imprisoned for criticizing the mayor of Atiquizaya in one of her columns and later, in Guatemala, she was also imprisoned for several months for accusations of collaborating with the planning of a coup d’état.

In 1921 she published the book Escible. Aventuras de un Viaje a Guatemala where she narrated her trip to Guatemala during the last months of the dictatorial government of Manuel Estrada Cabrera. She also published the books Inmortal, Amores de Loca and Payaso literario en Combate. At the end of the 1920s, she founded and edited the newspaper Redención Femenina, where she expressed her defense of women’s rights as citizens. She also published poems in several newspapers in the country.

In 1930, she revolutionized Latin American politics by running for the presidency of El Salvador as a single, indigenous mother with little formal education. This was a country where women could not vote. Her motivation was to change the situation of peasants in her country and above all, to fight for the rights of peasant women. She was “proud to be a humble Salvadoran Indian,” as she said when she launched her candidacy.

Ayala’s candidacy was repudiated by many. The newspapers of the time caricatured her and branded her as crazy, illiterate and a “bochinchera” (brawler). She had allies, such as the students who cheered for her and the founder of the newspaper La Patria, Alberto Masferrer, with whom she shared feminist and anti-imperialist ideas and who defined her cause as “noble and just.” She said that her government plan, which had 13 points, was not inferior “to those of other candidates who take themselves seriously.” In the plan, she promoted public education, support for the working class, women’s right to vote, non-discrimination against illegitimate children and the suppression “as much as possible” of aguardiente (alcohol).

Her candidacy did not prosper because the Supreme Court determined that women did not have the right to run for public office. Prudencia Ayala died in July 1936 and remained in oblivion for more than half a century until a coincidence changed her destiny. One of her sons, in 1996, saw a photo of her in an exhibition at MUPI (“Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen,” a museum that preserves El Salvador’s historical memory) and told the museum’s director that his family had a trunk filled with his mother’s writings and objects. This is how the history, writings, and personal objects of Prudencia Ayala became known by the public and were used by the museum to reconstruct her legacy.

Prudencia Ayala went from being the “crazy” woman who ran for president to a brave woman filled with the spirit of rebellion and determination. She was a woman who fought for what she believed was right, generated a debate, and with courage, set a precedent in the struggle of Salvadoran women, paving the way for the political participation of Salvadoran women.

Long after her death, in 1950, women’s rights were established in El Salvador. It is vital that we honor the memory of the Salvadoran woman who scandalized the society of her time with her proposal to be President of El Salvador.

Currently, Prudencia Ayala has become a role model for Salvadoran women. A coalition of women’s groups, including the Mélidas, the Dignas, CEMUJER, and AMS, created the Concertación Feminista “Prudencia Ayala,” a group composed of more than 20 feminist and women’s organizations, as well as at least 70 independent feminists.

References:

Recent Comments